I have a poem guide for this Middle English alliterative poem as well as a translation into Present-Day English, both up at Poetry Foundation.

final digital projects

This semester I taught “Graduate Colloquium: Digital Humanities,” the required introductory course in our graduate certificate program in digital humanities. All my students chose to hand in a final digital project as opposed to a researched paper (though several of the projects involved a lot of research!). I’m proud of the class’s efforts and wanted to record and share their public websites.

Thanks to the Digital Scholarship team at the Boston College Libraries and others around campus who worked to support these projects this semester.

/

France, Spencer. “The Homogenic History of the Hardy Boys.” [Voyant Tools / Wix]

Green, R. “Mapping Sacred Heart: Visualizing the Parish Census.” [ArcGIS / Google Sites]

Mills, Mackenzie. “Tracing Spiritualist Ideas 1840-1900.” [ArcGIS]

Paviwala, Munirmahedi. “Tracing Agricultural Change in South Asia (1500-1750 CE).” [ArcGIS / R]

Steacy, Fiona. “Mapping New England Literature.” [Google Maps / WordPress]

Zehner, Katie. “The Grave of Mr. Joseph Tapping.” [3D Scanner App / Weebly]

Zhu, Alexander. “The Temple of Mars: A Recreation of the Temple of Mars from the Knight’s Tale by Geoffrey Chaucer.” [Minecraft / Blender / Google Sites]

new poetry chapbook!

I am thrilled to announce the publication of my new poetry chapbook Chanties: An American Dream, from Bottlecap Press. Chanties weaves together different threads of my interests and our collective experiences of living on this planet. The book has been over a year in the making, and I’m excited to share it with you all. You can purchase it today for only $10 here!

Chanties: An American Dream is a shipboard reverie about the American boat we’re all in. Prose poems, lists, and lyrics find their sea legs while musing on a photograph of a lover left on shore. In a contemporary moment when the deep reaches of the forest already belong to IKEA, the ocean beckons. “The depths turn electric.” Responding to the impasse of subjective expression in contemporary lyric theory, these poems are scored in a national “first-person choral.”

Inspiration comes from past and present voyagers on these waters: Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Allen Ginsberg, Elizabeth Willis, Claudia Rankine, Ben Lerner, and Solmaz Sharif. The epitaphic concluding poem monumentalizes literary missed connections, ships passing in the night. “Here lies all your scholarship. Here lies your poetry.”

new poem

I have a poem up at Rob McLennan’s blog dusie. It’s from my forthcoming chapbook Chanties: An American Dream and is inspired by a trip my family took to Kefalonia in the Ionian Islands of Greece. The poem is called “Shore Leave from the USS Lineage.”

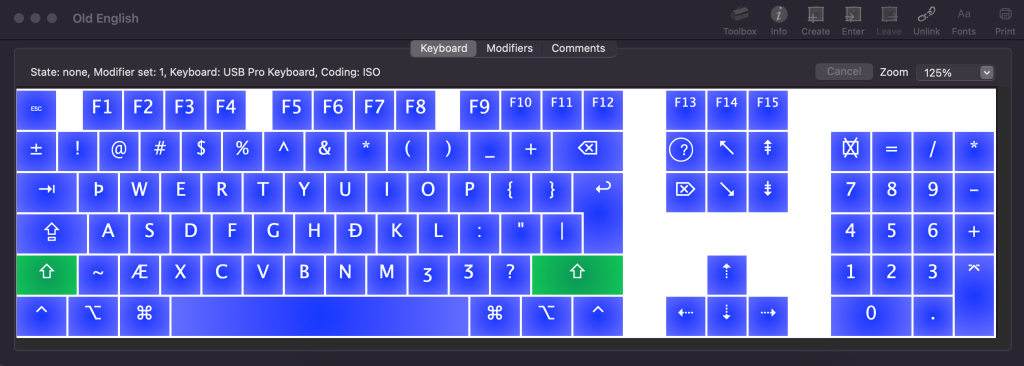

Middle English keyboard

I have defined a custom input source (aka keyboard layout) for Mac OS to enable me to type the premodern English characters ash (æ, Æ), eth (ð, Ð), thorn (þ, Þ), and yogh (ʒ, Ʒ). This is essential for my research, as otherwise I would have to copy and paste each character each time I type a block quotation or produce an edition of a poem. Now that I’ve gotten used to the custom keyboard I can type Middle English as fast as I type Present-Day English.

I defined the keyboard using the following substitutions: ash mapped onto z, eth mapped onto j, thorn mapped onto q, and yogh mapped onto < (lowercase) and > (uppercase). (The letters j, q, and z are rare in Old and Middle English.) If I had it to do again I might have mapped yogh onto x, also rare in Old and Middle English; but I am too used to the layout to want to change it now. I previously replaced v, which is not used in Old English, with wynn (ƿ, Ƿ). As I work more in Middle English than Old English these days, and wynn went defunct before the Middle English centuries, while v was used in more words, it is more important for me to have v available within the custom keyboard.

Here is the latest version of my keyboard layout in .keylayout format for anyone to use. Maybe this will be helpful to the medievalist readers. If you’d like to modify it at all, I recommend the program Ukelele.

To install on a Mac, copy the file into Library > Keyboard Layouts or create this subfolder. Then activate the layout by visiting System Settings > Keyboard > Text Input > Input Sources > Edit > “+.” The custom layout should appear under Others with the name Old English. It is then a simple matter of defining a keyboard shortcut to toggle between the regular layout and the Early English one. I use command + spacebar, which is convenient.

You must be logged in to post a comment.