I presented a short paper at the MLA in Vancouver, in a roundtable session entitled “‘Real’ Old English?” Thanks to the MLA Old English Division Committee for the invitation. I reproduce the paper in full here:

In the next seven minutes, I would like to convince you that real formalism and real historicism really are, or really should be, one and the same critical practice. Our idea of what counts as knowledge about early English literature will be enriched by integrating formalist and historicist methods. Those of us who work on prosody and poetics are used to being admonished that formalism needs to be historicist. I agree. But I am equally interested in affirming that historicism needs to be formalist.

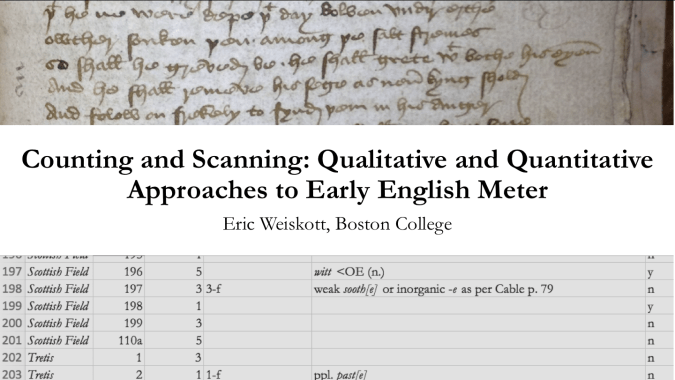

Here are two concrete examples of the opportunity for methodological integration, drawn from my research on the alliterative tradition. First, the most famous theory of Old English meter, Sievers’s Five Types, is an ahistorical formalism. It prescribes the same metrical norms for Cædmon’s Hymn in the seventh century as for the Death of Edward in the eleventh. What is worse, Sievers based his theory on Beowulf, an undated and possibly idiosyncratic poem. Geoffrey Russom’s word-foot theory and Nicolay Yakovlev’s morphological theory each represent an improvement on Sievers in that they each allow for metrical change over time.

Second, the marginalization of eleventh-, twelfth-, and thirteenth-century English texts reflects an Old Historicism that sought to align literary history and political history. The Normans conquered England, and English literature began to decay—or so the thinking goes. More recent scholarship problematizes this reductive view by emphasizing the dynamism and continuity of literary forms across the artifactual boundary of 1066. Indeed, this emergent research paradigm has begun to suggest the incoherence of the received period terms ‘Old English’ and ‘Middle English’ as such. The forms of literature explored by newer scholarship are material and intellectual (as in Elaine Treharne‘s work on twelfth-century habits of reading and transcription) but also linguistic and metrical (as in Yakovlev’s dynamic theory of the meter of Lawman’s Brut, which he also directly connects to his theory of Old English meter). In these and many other ways, historicizing literary form and formalizing literary history are complementary and interrelated research priorities.

For Old English to be real or really important, these large ideas and specialist debates must also work their way down into our pedagogy. Our undergraduate students want formalism, need historicism, and deserve both. As their first (and likely their only) teachers of Old English, it behooves us to introduce current understandings of literary form, while highlighting the problem of historical difference. Ideally, as I have been suggesting, these priorities coincide. I tend to initiate classroom discussions with prompts like, “Imagine a time before the invention of rhyming English meters,” or “Now that we have moved from the tenth century to the twelfth, which forms of language or literature seem different, and which seem the same?” This approach signals to students that the appreciation of literature as literature and the exploration of literary history as history are not somehow separate endeavors. This is, I submit, one of the most profound lessons we can impart to students who may be passing through our seminars to fulfill historical requirements within the English major. Our students will get the most out of Old English when they can encounter literary form as a historical phenomenon and understand literary history as an accretion of forms and styles. Form as history: history as form.

I have already indicated how recent work from within our field is pushing the field’s overdetermined historical boundaries, reconnecting ‘Old English’ with later forms of English language and literature. By way of conclusion, I’d like to discuss one way in which we might use the conjunction of form and history to enter into a meaningful conversation with our colleagues in later periods. The emerging field of ‘historical poetics’ proposes to historicize meters and discourses of the literary in order to reconfigure literary history. Currently, historical poetics is most strongly associated with the study of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British poetry, as in the work of Simon Jarvis and Yopie Prins. Engagement with the methodology of historical poetics on the part of Old English specialists would, I think, be mutually beneficial. The modernists have much to teach us about the microstructure of literary history; and we have much to teach them about the longer genealogies of form that connect early English literature to the complex literary cultures of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Moreover, medievalists are uniquely positioned to analyze the differences between practice and theorization of literary form, since medieval authors, in contrast to modern ones, practiced literary form at a time when vernacular poetics had not yet become an academic subject or a sustained cultural discourse. Many of us are already engaged in research that historicizes form and formalizes history. Again, unlike our modernist colleagues, we have never had the luxury of taking for granted the material, intellectual, linguistic, or metrical contexts of the literature we study. Historical poetics presents an opportunity for us to articulate the value of our field to English studies as a whole.

I have also deposited the paper in MLA CORE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.