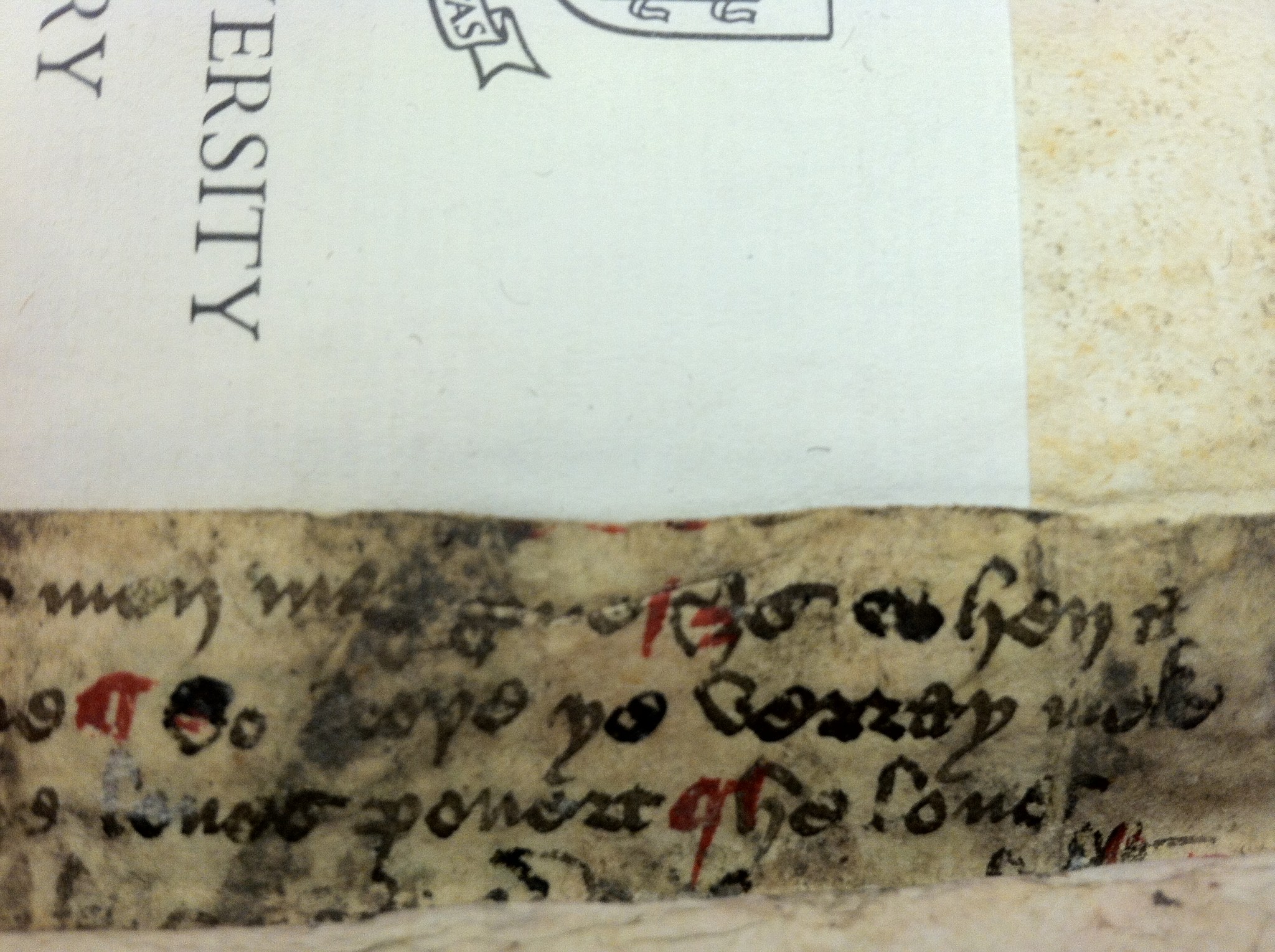

My article, “Alliterative Metre and the Textual Criticism of the Gawain Group,” appears in the Yearbook of Langland Studies. Here’s the opening frame of the essay:

Recent studies have gone some way toward solving the riddle of Middle English alliterative metre, while at the same time uncovering evidence of continuity between Old English metre, Early Middle English alliterative metre, and Middle English alliterative metre. The principles governing the alliterative metre in the fourteenth century have been discovered and elaborated by a series of distinguished scholars: Hoyt Duggan and Thomas Cable in the 1980s and 1990s, followed by Judith Jefferson, Ad Putter, Myra Stokes, and Nicolay Yakovlev in the 2000s. The new metrical scholarship refocuses questions of literary history, poetics, and the cultural meaning of metre. In particular, the alliterative tradition appears to have been both more durable and more dynamic than proponents of a so-called Alliterative Revival supposed.

The new metrical models should interest the textual editor because, cautiously applied, they can supplement other considerations in the editing of alliterative verse texts. This essay reexamines Malcolm Andrew and Ronald Waldron’s authoritative edition of Cleanness, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Certain readings, both editorial and scribal, now seem implausible in light of current metrical theory. In addition to their intrinsic interest for students of the Cotton Nero poems, my proposed emendations and non-emendations are meant to function as a case study in the application of metrical theory to textual criticism. I take as my models a recent essay by Stokes on metre and emendation in Gawain and another by Jefferson and Putter on the text of the Middle English alliterative poem Death and Life, though my understanding of alliterative metre and my editorial sensibilities do not accord with theirs in every detail. In what follows, I summarize two points of general agreement among metrists, review the stress assignment and metrical phonology of Middle English alliterative poetry, and track Andrew and Waldron’s understanding of alliterative metre across the five printings of their edition. The second section presents ten verses in the Cotton Nero poems in which metrical theory can be of service to textual criticism. In the third and final section, I review a recent essay by Ralph Hanna and Thorlac Turville-Petre and discuss two promising avenues for future research at the intersection of metrics and textual criticism: the alliterative metre of Piers Plowman and the shape of the a-verse in Middle English alliterative poetry.

Throughout, I argue that metre can be utilized as one dimension of editorial assessment in conjunction with other considerations, while remaining circumspect about its ability to furnish independent grounds for emendation. This essay seeks to lay the groundwork for future research by consolidating progress in alliterative metrics, illustrating the application of metrical theory to textual criticism in ten individual passages in the Gawain group, and exploring the theoretical and methodological implications of cooperation between metrics and editing. The combination of practical, theoretical, and methodological discussion is meant as a provocation to future studies that might address broader topics, for example the Gawain-poet’s metrical habits in general, as well as narrower ones, such as metrical approaches to a locus desperatus in the text of Piers Plowman.

Andrew and Waldron’s edition makes a worthy candidate for scrutiny, because it represents a comprehensive editorial achievement. I hope to show that metrical considerations can aid in the identification of implausible editorial emendations. More generally, I argue that the dialectical process of editing with metrical theory and theorizing metre with edited texts should serve as a reminder of the limits of cooperation between these fields of inquiry and hence the provisional nature of both metre and edited text as historical reconstructions. Andrew and Waldron’s hugely influential edition remains indispensable, but its lack of engagement with metrical theory on the level of editorial praxis undermines the plausibility of its text in several places.