I thought I’d give a progress report and some backstory on my current book project, Unheard Melodies: Apophatic Poetics in English Literature.

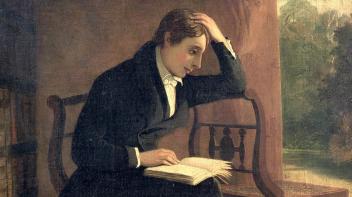

I was an experimental poet before I was a scholar of premodern England. In this book, for the first time in my scholarly career, I am paying critical attention to the contemporary American lyric poetry that I have been reading, teaching, and writing for years. The point of connection is what I call apophatic poetics: literature’s invitation to apprehend the inapprehensible, as in John Keats’s “On a Grecian Urn”: “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter.”

I argue that apophaticism entered English poetic practice in premodernity via apophatic (or ‘negative’) theological discourse (on which see Turner). However, I’ve organized the book conceptually rather than historically, and it’s not important for my argument that any particular author have theology in mind. In fact, it’s more interesting when they don’t. When Lerner writes a verse essay theorizing “the negative lyric” (59-67), I think he is thinking of Adorno and Hegel, but his use of negation has more in common with pseudo-Dionysius.

I’ve come to see Keats as the crucial hinge between premodern and contemporary apophatic poetics. His famous term negative capability names a disposition that lies behind many of the works I discuss in the book. Keats’s sweet unheard melodies sound an awful lot like the heavenly/mental music described in the Prick of Conscience, Pearl, Margery Kempe’s Book of Margery Kempe, and William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Centuries later, Dickinson echoes Keats (Miller 198, 684):

This World is not conclusion.

A Species stands beyond—

Invisible, as Music—

But positive, as Sound—

It beckons, and it baffles—

Philosophy, don’t know—

And through a Riddle, at the last—

Sagacity, must go—

and

The words the happy say

Are paltry melody

But those the silent feel

Are beautiful—

Dickinson’s “through a Riddle” refers to 1 Corinthians 13:12, “Now we see through a glass darkly [per speculum in enigmate],” which has emerged for me as a key scriptural reference-point for apophatic poetics. Speculum and enigma are the names of early literary genres, mirror for princes and riddle. The works I consider in the book all, in different ways, understand themselves to be inadequate, reflecting the world (like a mirror) but with mysterious distortions (like a riddle).

This is also my Piers Plowman book. I consider William Langland the grandmaster of apophatic poetics. Ejecting his poem into the undefined negative space surrounding familiar languages, literary forms, genres, motifs, texts, doctrines, devotional practices, and historical persons and events, he weaves a text almost entirely out of what I call apophatic effects. I read Piers Plowman in enigmate, following Gruenler and other modern commentators but also echoing the English rebels of 1381, who discerned under the surface of the poem an incitement to insurrection, and John Bale, who says he found in Piers Plowman both prophetic grandeur and an abundance of figurative language (Bale’s word is similitudines ‘analogies,’ another keyword of my book).

Part I of the book, now drafted, is a survey of forms of apophatic effects: unpronounceable syllables, metrical duck-rabbits, unreadable novels, and more. Authors and texts considered in part I include Anne Carson, Beowulf, Edmund Spenser, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Wallace Stevens, Victoria Chang, and Vladimir Nabokov. Part II, yet to be written, will discuss the careers of six poets, three from the fourteenth century and three US-based poets born in the middle of the twentieth: Geoffrey Chaucer, Bob Dylan, Langland, Claudia Rankine, Elizabeth Willis, and the poet of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I’m going to have fun comparing and contrasting across the six-hundred-year gulf.

further reading

Dickinson, Emily, and Cristanne Miller, ed. Poems: As She Preserved Them. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Gruenler, Curtis. “Piers Plowman” and the Poetics of Enigma: Riddles, Rhetoric, and Theology. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2017.

Lerner, Ben. Angle of Yaw. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon, 2006.

Turner, Denys. The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

You must be logged in to post a comment.